We got a Jenny Lind crib. At the time, it was the only simple crib we could find that wasn't Ikea or David Netto. We got it from Schneider's when they were still in Alphabet City. He said that it was very popular among the crib painting artists, who'd buy a plain, hardwood Jenny Lind for $200, then Shabby Chic it up and sell it at ABC Carpet for $1,500. Since I can't stand ABC Carpet, I had no idea, but it felt like a deal and it was ready for immediate delivery. And it was totally fine. Of course, the crib world's changed in six years [wow], and we passed our still-solid crib on to a single mom friend. But I can't quite shake my nagging curiosity about why and how the Jenny Lind crib is called the Jenny Lind crib in the first place.

We got a Jenny Lind crib. At the time, it was the only simple crib we could find that wasn't Ikea or David Netto. We got it from Schneider's when they were still in Alphabet City. He said that it was very popular among the crib painting artists, who'd buy a plain, hardwood Jenny Lind for $200, then Shabby Chic it up and sell it at ABC Carpet for $1,500. Since I can't stand ABC Carpet, I had no idea, but it felt like a deal and it was ready for immediate delivery. And it was totally fine. Of course, the crib world's changed in six years [wow], and we passed our still-solid crib on to a single mom friend. But I can't quite shake my nagging curiosity about why and how the Jenny Lind crib is called the Jenny Lind crib in the first place.

Because the obvious, quickest explanation ["Jenny Lind was the most famous soprano of the mid-19th century, duh."] doesn't really answer the question. So I have unleashed my crib-nerdiest documentary-and-research skills on solving a mystery almost no one really cares about, and the answer to which is probably sitting in a mouldering banker's box containing the archives of the marketing department of a third-tier crib manufacturer in the 1960s. Thus, with apologies to Errol Morris, and the promise that this is probably not the first of a seven-part series., let's begin:

Jenny Lind, aka "The Swedish Nightingale," was an opera singer who P.T. Barnum transformed into a pop media sensation in 1850. Her US tour, booked, promoted, and manipulated by Barnum, created a frenzy akin to The Beatles, Madonna, Brangelina and the Pope combined. Lind, who Barnum hyped for her purity and piety as well as her angelic voice, was the original celebrity endorser, even if she didn't know it. Here is a paragraph from an awesome 2007 NY Times article on Barnum which would be the last word on Jenny Lind cribs--if it weren't wrong:

Jenny Lind, aka "The Swedish Nightingale," was an opera singer who P.T. Barnum transformed into a pop media sensation in 1850. Her US tour, booked, promoted, and manipulated by Barnum, created a frenzy akin to The Beatles, Madonna, Brangelina and the Pope combined. Lind, who Barnum hyped for her purity and piety as well as her angelic voice, was the original celebrity endorser, even if she didn't know it. Here is a paragraph from an awesome 2007 NY Times article on Barnum which would be the last word on Jenny Lind cribs--if it weren't wrong:

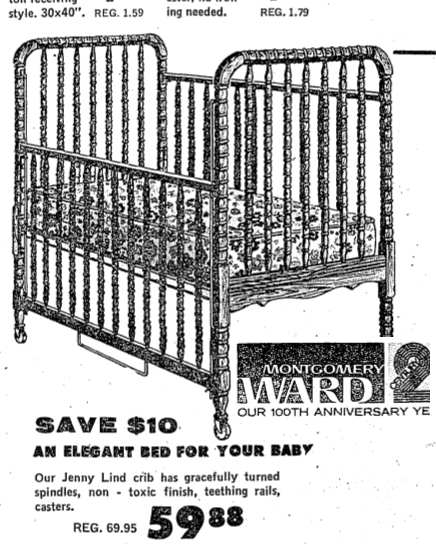

For six months before her arrival Barnum used every marketing and advertising means at his disposal to whip up a fever of "Lindomania." He filled newspapers with articles of her beauty and piety. He ran Jenny Lind poetry contests. An entire merchandising industry sprang up to churn out Jenny Lind hats, Jenny Lind parasols, Jenny Lind face cream and the Jenny Lind crib, which you can still buy today. [emphasis added, duh, as if the Times would bold that themselves]According to the PT Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, which has an installation of Lind products, souvenirs, and materials, manufacturers would send their product to the saintly singer with their humble compliments, and then advertise how she loved them. [Celebrity-chasing publicists, be proud! You are part of a rich, storied American tradition of just making shit up for money!] But while they have later mentions of beds, there is nothing about a crib. And while I'm sure it existed earlier, the first print mention of a Jenny Lind Crib I've been able to find is a Montgomery Ward advertisement from 1972, over 120 years after Lind left the US. [below, from the Chicago Daily Defender, 10/21/72]

Wikipedia doesn't cite a source for its crib claim, but at least it connects Lind with the spool-turned furniture style:

During her visit to America, she was reported to have slept in a bed with turned spindles, leading to the naming of the style of crib or baby bed with vertical bars on all sides as a "Jenny Lind crib."And here, perhaps, is that bed, photographed this summer at the Geneva Historical Society's Rose Hill, a 19th century house museum in New York's Finger Lakes region. John Marks, the GHS's collections curator, sent a 1969 article ["Prouty Chew displays original Jenny Lind bed", The Geneva Times, Feb. 27, 1969] about the bed's acquisition and exhibition in another, awesomely named GHS museum.

To counteract the rumor that he was "a cheap showman with no cultural contacts," PT Barnum took Jenny Lind to his estate in Connecticut and then made the circuit to visit

his most cultured and sophisticated acquaintances in Connecticut...at the start of her tour. Among her many stops, Miss Lind stayed at "Greystone, in Darby, Conn., with the Shelton family. The bed was the one in which she slept and after her departure, local cabinetmakers copied the style. The "spool bed" and other pieces of furniture featuring spool work have since been known as "Jenny Lind furniture."The Sheltons of Darby were the family of Edward Shelton, who owned a large pin factory and gave the adjacent town of Shelton its name. In the early 1900s, a guy named John Robert Lightfoot, moved his family to Shelton/Darby, to run the factory. They lived next door to Greystone. In 1910, the Sheltons decided to give the Jenny Lind bed to Lightfoot's daughter Jane, who was known as "Little Jenny." At least that's how Jane Lightfood Beaumont told it in 1968 when she donated her bed to the GHS.

Though there is no documentation of it, the basic contours of the Beaumont's story check out. Lind did visit Iranistan, Barnum's hilariously named Bridgeport estate early in her tour. Lightfoot's name shows up in Darby newspaper accounts of the time. For reasons known only to those familiar with the whirlwind life of a suburban historical society librarian, though, neither the Darby Historical Society nor the Shelton Historical Society were able to say whether the archives of the local papers in their little hamlets recorded a visit by most famous woman in 19th century America in the fall of 1850.

Of course, putting Lind in Darby or at Greystone isn't the same as putting her in the bed. And even if we assume she did sleep in it, there are still gaps and date discrepancies in the story. For one thing, the popularity of the Lind style had clearly preceded the arrival of Lind herself.

The GHS's Marks cited Thomas Ormsbee's classic Field Guide to Early American Furniture (1951), which says the spool bed "is sometimes referred to as a 'Jenny Lind' bed since it was in vogue during her American concert tours," and puts the dates of its popularity at 1840-1865. And here's an undated Antiques Digest article towing that line:

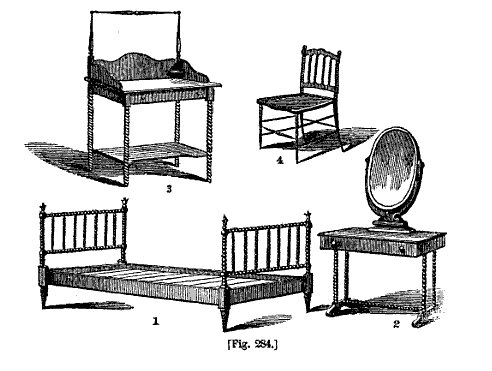

This spool-turned cottage furniture came into fashion about 1840 and continued into the 1880's. A familiar part of home furnishings between 1840 and 1865 was the low-post spool bed. Sometimes referred to as a "Jenny Lind" bed because it was in fashion at the time of her American concert tours, the early ones had four low posts with headboards and footboards either solid or constructed of short slender spindles turned to match the posts.Which sounds a lot like the Shelton/Lightfoot bed. These simplified turned spindles were the result of automation beginning as early as 1820. That's when cabinetmakers across New England began replacing pedal-powered lathes with steam- and water-driven technology. By 1850, the earliest furniture factories were forming, and these spool-turned pieces were some of the first manufactured--as opposed to crafted--furniture. Which makes it some of the most likely furniture to be mass-marketed using an association, real or imagined, with a big celebrity name.

Except that it wasn't. By 1859, when he published his influential style guide, The Architecture of Country Houses A.J. Downing said spool-turned furniture [above] "has now become common in the cabinet shops, is afforded at very low prices, and is particularly well suited to cheap cottages and farmhouses in the Bracketed style." Downing doesn't mention Lind at all.

From the 1860s until the early 20th century, the only newspaper or advertising mentions of Jenny Lind and furniture are a few accounts of visits to the "aging prima donna's" London home, like this hyperventilating Washington Post reporter in 1880--

Embowered by trees and flowers, the home of Jenny Lind looks just fitted to be the peaceful retreat for one who has drained to the very dregs the world's intoxicating cup of honors and applause. In the elegant drawing-room, hung with pictures and tastefully decorated with old china, artistic draperies, etc., I found a lady whose blue eyes and kindly smile bore me back at once over the waste of some thirty years.--or to a pool hall game ginned up to circumvent anti-gambling laws. In 1871, Jenny Lind's accompanist-husband Otto Goldschmidt famously sued a British paper for libel over charges that he'd gambled away his wife's fortune. He gave testimony that in fact, "He had never been near a gambling hall or a billiard table, and had no time for such pursuits."

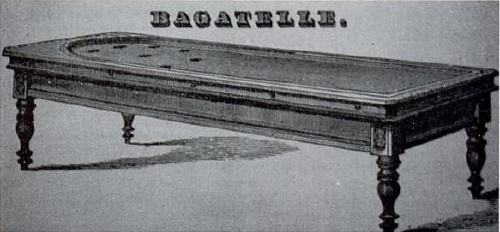

When New York outlawed four ball, a bagatelle/billiard-like table game which was a precursor to shuffleboard and pinball, in 1879, saloon owners circumvented the law by introducing a fifth ball. They called this chaste, upstanding, pious, and totally non-gambling-related game Jenny Lind.

[Update: hmm, while looking for a picture of an actual Jenny Lind table, I found a record of Bartender vs. State, the best-named case the Indiana Supreme Court heard the entire year of 1875, that found the defendant had not broken an anti-bagatelle, anti-pigeon-hole statute because the table in his fine establishment was clearly a Jenny Lind table, and Jenny Lind was clearly a different game. This calls into question New York's longstanding reputation as the birthplace of the technicality-exploiting gambling industry.]

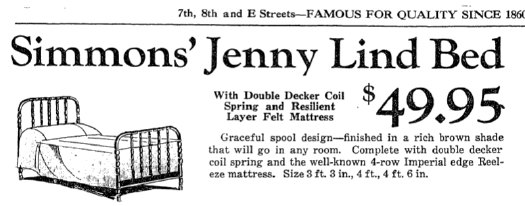

The earliest mention of a "Jenny Lind" bed, is from a 1925 ad for Karpen furnituremakers in the Washington Post. Instead of the post-and-beam construction of the 1850's spool beds, the Karpen daybed, and the Simmons' Jenny Lind bed advertised in 1929 [below], had the bent, turned-all-over shape of the modern cribs.

So is there a connection, then, between the Shelton's Lind Bed, which stayed, unreported, in the family until they gave it to the help in 1910, and which remained in private hands in upstate New York until 1969, and these different-looking, department store Jenny Lind beds which appeared in the 1920s? Why did various manufacturers in the 1920s call their bentwood, spool-turned beds "Jenny Lind"? American furniture tastes went through two big "antique" periods, one around the 1870s and 80s, when the US Centennial celebration set off a colonial revival that displaced the gothic/country-associated spool furniture of the previous decades, and again in the 1920' and 30s when the Rockefellers opened Colonial Williamsburg, towns across Connecticut began refashioning themselves as colonial havens, and my hapless ancestor Ethan Allen had his name hijacked by heritage-peddling furniture opportunists. Until I see some evidence to the contrary, I suspect that Jenny Lind suffered the same fate. But at least the search is joined.

Have I told you lately that you are a geek and that I adore you for it?

Wow, quite the treatise.

However, I can't help but notice how the "Jenny Lind Bed" looks a lot like the "Abraham Lincoln Deathbed".

http://showcase.netins.net/web/creative/lincoln/education/abed.htm

I am thinking "Abraham Lincoln Death Crib" would probably not be a bestseller.

You are insane. In a good way, but still: bananas.

Cool -- I'd been wondering this recently as I'm getting our old Jenny Lind crib ready to pass on.

I have been amused by the many people on eBay who look at the crib (by Evenflo, who apparently have changed names to DaVinci) and think that "oak" describes the wood, rather than the wood color. It's surely rubberwood.

Thanks for the shout-out - you may be nuts, but you're the reason museums & archives stay in business! Call anytime.