The original title of Marcel Breuer's December 1943 article for California Arts & Architecture was "Design for Postwar Living." But he changed it to "On a Design of a Bi-Nuclear House." [Actually, on the typescript, he wrote "By Nuclear," which is either a non-native English speaker's error, or a slip revealing Breuer's top secret involvement in the Manhattan Project.]

The highly technical bi-nuclear house would ideally suit the needs of "the postwar man" who will "tend to use his mechanical equipment to supply color and balance to his life, especially if he is returning from the war. His mechanized world, his job, will probably only keep him busy not more than three or four days a week. He will quite naturally want to utilize his free time around the house, which ought to be a more versatile instrument."

In 1943 Breuer envisioned the postwar house split into "two separate zones," one for living and socializing [including "eating, sport, games, gardening, visitors (and) radio"], and the other for "concentration, work, and sleeping." ["The bedrooms are designed and dimensioned so that they may be used as private studies."] After all those years in bunks and tents, it sounded like the postwar man needed his space, someplace quiet to be alone.

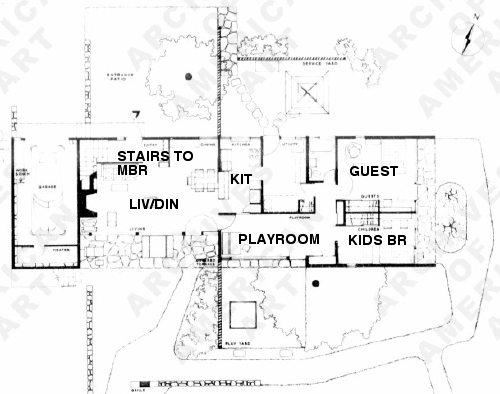

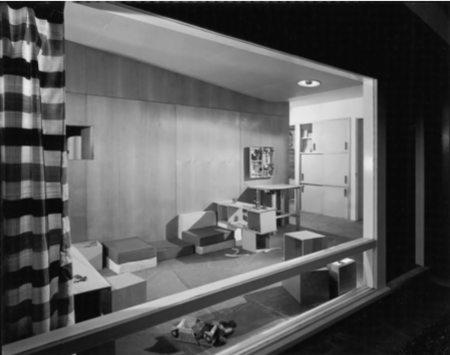

But somewhere along the way, the zones in the bi-nuclear house shifted, separating not public and private life, but parents--especially dads--and kids. Breuer's 1949 prototype house in the Museum of Modern Art sculpture garden didn't have "zones" split by an entrance foyer, but the parents' bedroom was alone upstairs, while the children's room and the playroom [below, with awesome Creative Playthings maple block furniture] were on the opposite end of the house--right next to the kitchen, so mom could keep an eye on the kids. [I can't find my Breuer house brochure to scan it cleanly, so I'm stuck annotating this watermarked plan from the Archives of American Art.]

Then there's this, Philip Kennicott writing about a 1959 Breuer house outside Baltimore in this month's Dwell:

It's a textbook example of Breuer's classic "bi-nuclear" house, a division of the home into spaces for adults and children. As you enter, through a ten-foot glass gap cut into the stony Zen blankness of the house's 131-foot-long western wall, you confront an architectural Parents' Bill of Rights: kids to the left (bedrooms, bath, and a playroom), adults to the right (living room, dining room, kitchen). "You want to live with the children, but you also want to be free from them, and they want to be free from you," wrote Breuer in 1955, a deliciously dated understanding of the familial balance of power.In my so-far unsuccessful search for the source of that Breuer quote, I haven't found any discussion of this apparent evolution of the bi-nuclear house from public vs private to parents vs kids. I wouldn't expect Breuer to suggest that postwar man could spend his four days/week off work taking care of the kids, but it seems like there's a lot to be said about the way postwar modern design interacted with the dynamics of the postwar modern family.

Typescript of article: "On a Design of a Bi-Nuclear House," published in California Arts and Architecture, 1943 [aaa.si.edu]

Museum of Modern Art Exhibition, New York, New York, House in Museum Garden, 1949 | photos of plans and drawings [aaa.si.edu]

Marcel Breuer, Hooper House II [dwell.com]

Previously, Eliot Noyes: Midcentury Family Modernism

the quote is likely from 'sun and shadow' his 1955 collection of plans and ideas. not the sharpest writer, Marcel, but some interesting stuff.