Sunday afternoon, the kid was kind of high, and she'd been acting up all day, putting herself at repeated risk of not being allowed to go to the big Boo at the Zoo party last night if she kept it up. And after losing the two hours of sleep that counted the most--3-5 AM--with a screaming sick baby, Jean was not in the most patient of moods. So I figured I'd give us all a little quiet time by taking the kid out to a museum, any museum.

We decided on the Phillips Collection over the Hirshhorn because it was closer, it didn't involve parking, and it was quick. We could pop into the Rothko Room and the installation of Jacob Lawrence's The Migration Of The Negro and be back home in time to carve the pumpkin.

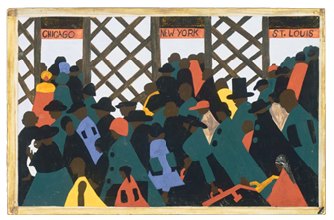

The kid knows Lawrence's work and the one-line synopsis of Migration Series--people moving north with their rectangular suitcases--from her The Art of Shapes boardbook from MoCA. But she didn't care too much about all-Migration book when I bought it last winter. The Great Migration is a children's book containing all 60 paintings in Migration Series: the 30 odd-numbered panels belonging to the Phillips, and the 30 even-numbered panels from MoMA.

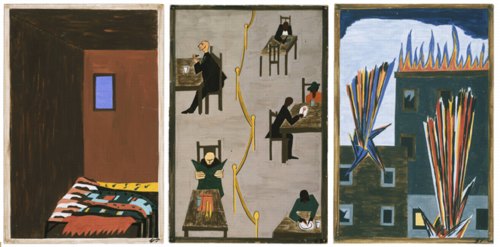

But the Phillips made some calls or whatever, and beginning in May, they put entire series on view. The kid and I, with K2 occasionally in tow, made at least half a dozen visits, and she really took them in. Lawrence gave each painting a caption, and as we moved from panel to panel, the series became like a familiar book. And we'd talk about at how Lawrence painted woodgrain, how swirls were vegetables in the field, at how a few squares become a row of buildings.

Sunday turned out to be the last day all of Migration Series was together before MoMA's half got put back in storage. [It used to be on permanent display, filling a wall on the third floor of MoMA's atrium.]

Lawrence covered a lot of ground in the Migration Series, and I'd edit panels or captions out of the story to suit the kid's age. There are panels depicting lynchings and race riots and beatings, which we'd skip, and paintings of discrimination in southern courts, strikebreaking, and arrests which I'd soften up. I could see her understanding growing, though; once this summer, she asked if this was a "real story" or a "pretend story." And so we talked about lunch counter-level discrimination, people getting treated differently because of the color of their skin or their hair.

This last time, though, I decided I'd read each of Lawrence's captions straight. [Well, as straight as they were printed on the wall, anyway. The term "Negro" has been removed from the work's captions, even its title.] I felt she was ready. We've talked about war, death, violence, good and bad. She knows what the law is, and what crime and jail are. She's seen anger and fighting now, too, if only in the limited context of the playground, or in stories, or discussions of the news. And she has at least heard about the existence of slavery, and discrimination, even if the underlying notion of racism was still a mystery to her.

And that is a fact of the real world I've felt the strongest desire to shield her from, for as long as possible. As a rule, I don't write about the kid's preschool, mostly out of respect for her and her classmates' privacy, and also to keep the reporting/on camera aspect of blogging out of our relationships with the kids and their families. But I'll say that one of the primary reasons we picked the kid's school was its commitment to diversity, in terms of race, family composition, economics, and developmental levels.

The kids all learned to celebrate both their similarities and their differences. And it's been remarkable, almost euphoric, to watch the kid's formative reality take shape in a compassionate, supportive, egalitarian cocoon, where the variously shameful, outrageous, and complicated histories of discrimination and prejudice in our culture essentially didn't exist. And where the very idea that you would judge or hate someone because of their skin was totally alien.

When we'd look at a painting that directly addressed racial discrimination, I could tell the kid was hearing, but not getting it; as if something as unjustifiable as racism could ever make sense. When we saw the lynching panel, which depicted a black body hanging from a tree, and the race riots in East St. Louis panel, which showed people getting beaten, it was easy enough for her to understand that hitting, beating, and killing were wrong; but even when I laid them out, she clearly did not comprehend the race-driven motives on display.

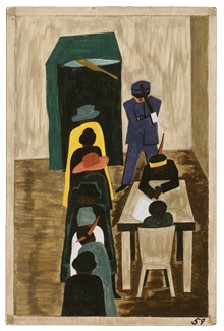

The caption on panel no. 59 reads "In the North, they [the Negro] had freedom to vote." The painting depicts a registration table and a voting booth with a line of black figures waiting their turn. In the small, crowded gallery, holding my daughter, I lost it, and had to read the text in fits and starts through my tears. The kid watched me pausing, but didn't say anything. So I took a couple of breaths and explained how, during the Migration, even until right before I was born, it was hard, even impossible, for people to vote in some places if they had brown skin.

The Great Migration story began in the land of slavery and Civil War and Jim Crow. It involved crops and floods and violence and jobs and housing and education. But as Lawrence told it, the culmination, the happy ending, such as it was, was voting.

I grew up in part of that South, where we didn't celebrate Lincoln's birthday, where blacks weren't allowed in the pool, and where I was bussed across town to an all-white school-within-a-school in technical compliance but obdurate defiance of the US Supreme Court. I've traveled a lot of ground since I sang racist songs about Jimmy Carter with my little classmates, or since I cluelessly earned my Citizenship merit badge by volunteering in the office of my former senator, the vile bigot Jesse Helms. [As penance, I stayed registered as a Republican ever since, so I could vote against him twice, in the primary and the general election.]

I've earned my excitement over this year's election, but I've been wary of transferring it unfiltered to the kid, and this last experience in the museum was no different. When we'd walk to school last spring, and the kid and I would use the Obama and Hillary signs en route to practice letters and reading, and eventually to discuss the idea of elections, presidents, and countries. It felt important to me to not load too much "history" by describing either Obama or Hillary as the very first of anything; that excitement was for my generation, not hers.

To a girl born in 2004, a bi-racial man and a woman facing off for the presidency was not shocking, or novel or long overdue; it was normal. And that's remarkable to me.

The Phillips Collection site for Jacob Lawrence's Migration Series [phillipscollection.org]

Previously: Jacob Lawrence's The Migration of the Negro

That was beautiful.

I hope for your children & mine these things remain normal.

very nice

This brought tears to my eyes.

Each year, as predictable as the Great Pumpkin or Santa, the Girls get the Suffragette talk. They learn how women fought for the vote, and why it's so important. The have ALWAYS accompanied me to the polls, initially for convenience, but now for a reason.

This year, we have even so much more to celebrate.

I embrace with eagerness what will (hopefully) be the normality of our children's future.

Oy, we still have to get to that one. The caption for Panel No. 57 reads, "The female workers were the last to arrive North." So naturally, the kid goes, "Why?" That's the other cocoon she's living in at the moment. We will have some suffrage and feminism discussions soon enough, but for the moment, the kid's living in what Obama called in his first book, her "stretch of childhood free from self-doubt."

That was a great post, Greg.

I agree - this is a great post.

And I feel the same way about this election. I am so thankful that my kid gets to grow up knowing that a woman and a black man have more than a fighting chance to run for the highest office in this country. As recently as 15 years ago, when I was in high school and spending a lot of my time in groups that championed feminism and equal rights for minorities, this seemed like it was such a long way off, but it has finally happened. Here's to hoping that our kids don't even have the need for those kinds of groups when they get to high school. :)

Great post...we live in that state, and my kids are in a school that sounds a lot like yours. That had so much to do with why we chose to send them there.