Funny, I don't remember 1994 looking like the zany cruft on an Exersaucer. And I don't recall Post-Modernism retaining even half that credibility as long as it does in Steven Heller and Steven Guarnaccia's book, Designing For Children [first mentioned here]. But I do remember Baby Boomers being easily this self-impressed:

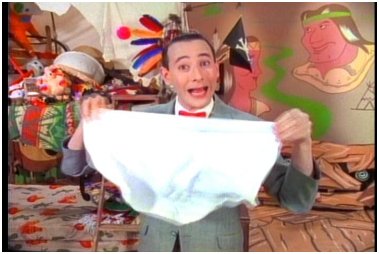

Only recently has a generation come of age that fully embraces a "Peter Pan Principle"--the idea that a child-like state of mind can and should be perpetuated, in this case through art and design. While this statement may seem to invalidate a long heritage of remarkable efforts in behalf of children, and appears to be biased in favor of our own generation, it can be argued that baby boomers have been more intensely involved in children's culture than previous generations, who had to slog through the muck of the Depression and mire of war, and that we are now continually bomarded with this culture through media that didn't exist for preceding generations.Fortunately for our children, we Gen X and Y parents are finally the generation that accurately identified the shortcomings and self-delusions of those who came [just] before us, and we've figured out how best to solve all the problems in the culture we inherited. Damn, we're good. There's a longer excerpt from DFC below. A warning, though: close objects in the rearview mirror are scarier than they appear. And as any visit to a bigbox store will still tell you, PoMo never did better than PeeWee's Playhouse:

Those of us who grew up in the postwar era have vivid memories of the bountiful merchandise dedicated to our enjoyment. It was a period when the great toy firms Mattel, Hasbro, and Marx began fighting for shares of the new market. One can still recall that the introduction of a remarkable new battery-operated toy made our collective mouths water with Pavlovian predictability. Yet it was also a time when progressive designers, many originally from Europe and some who were previously involved with avant-garde schools and workshops of the German Bauhaus or Dutch de Stijl, began to proffer alternatives to the aggressively commercial products on the market. Such graphic and industrial designers as Charles and Ray Eames, Ladislav Sutnar, and Raymond Loewy developed materials that fundamentally diverged from the hyperrealistic dolls, weapons, and other conventional fare that proliferated. The "well-designed" toys, such as Charles Eames's House of Cards, were created to help develop cognitive and intuitive skills. In reaction to the plethora of disposable gimmicks and gadgets that, frankly, made being a kid in the postwar years materially quite satisfying, a need for higher standards was recognized--a need not just for products that wouldn't break within minues of being removed from the box, but for ideas tha would both please and challenge children.Still, what kid would opt for a Creative Plaything, one of those handsomely designed yet static "educational" toys so popular with adults in the 1960s, over the plastic Rock-em-Sock-em Robots or other commercial action toys of the same period? Despite the push among enlightened adults for alternatives and the efforts of progressive thinkers to enhance life through effective design, even by the 1960s and 70s the resistance to good design was still strong among marketers--and children bombarded with mesmerizing advertising.

Actually, children had other, perhaps intuitive, reasons to prefer the mass-market aesthetics. In 1963, an issue of Design Quarterly (#57; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis) was devoted to children's furniture and showed stunning reproductions of elegantly proportioned modern forms from Denmark, Great Britain, and Sweden. These were promoted as paradigms of a new sensibility. In one photograph two children play with an Erector Set, which they've obviously taken out of a handsomely designed, very functional modular storage crate. The sterility of this ideal scene overwhelms even one sympathetic to modern design. For in trying to create a perfectly designed environment--one that an adult would surely accept--the childhood aesthetic was lost.

The modern dictum, "Form follows function" led to a belief in the rightness of simplified form, which in theory should apply to everyone regardless of age. Yet mature adults have different aesthetics than children do, and children have different preferences even among themselves. The problem with designing for children in the 1960s and early 70s was that many innovative designers were reacting to chaos and imposing a sense of order that was not instinctively in tune with children. Despite efforts to mold children into our own image, the most effective design is not based on sophisticated avant-gardisms but on qualities that somehow respond to the child within and without.

Only recently has a generation come of age that fully embraces a "Peter Pan Principle"--the idea that a child-like state of mind can and should be perpetuated, in this case through art and design. While this statement may seem to invalidate a long heritage of remarkable efforts in behalf of children, and appears to be biased in favor of our own generation, it can be argued that baby boomers have been more intensely involved in children's culture than previous generations, who had to slog through the muck of the Depression and mire of war, and that we are now continually bombarded with this culture through media that didn't exist for preceding generations. Rather than reinvent the child's environment through sophisticated methodologies that often owe more to some theory of functionalism than to childhood, many artist and designers today--baby boomers mostly--are revisiting their own experiences, reprising, assimilating, and synthesizing images and icons of the past three decades into a contemporary children's culture.